Keyboard Warrior

A decade of software development

24 July 2025

For the last ten years I’ve happily created experiences for different parts of the web. My meager abilities in web development were cobbled together over years of building layouts for Myspace and Tumblr, and a few odd jobs in college that required making minor changes to PHP scripts powering the Computer Science department website. It was enough to make a small portfolio, which I clumsily used to land an internship.

Internship

I worked at a budding company that was building tools for safer policing. After getting manufacturing off the ground for their hardware product, they brought a lone software development intern on board to develop proof-of-concepts for their real-time tracking software. I worked in a small windowless room that held a few shelves of electronic components and my desk. I had a trusty Dell laptop with an external monitor, a box full of GPS units, and a coffee mug.

My web skills at the time were limited to HTML, CSS, and a bit of PHP. There was little to no direct guidance on how I should go about my tasks, so I started with what I knew and expanded as needed. I built my first app by cobbling together an AngularJS frontend supported by a PHP and MySQL backend. The GPS units connected to a Python socket server that dumped all of the data into database rows, and the frontend polled the backend every half second to refresh the mapping software. I was wildly happy after I returned from a test drive with my GPS and the application worked, plotting my path in real-time. The implementation was nothing I’d be able to get away with today, but it was wonderfully naive and a great foray into web applications.

Gets Real

I got my next job after graduating at a medium-sized operation downtown. It was an entry-level software developer position on the frontend team of a real estate website. We cranked out the first version of a complete rewrite of the site, from a ColdFusion stack to an AngularJS frontend that targeted a NodeJS backend1. The end result was a modern looking site that was significantly faster to load. The opportunity arose at the end of this project to try out backend programming, something I was growing more interested in at the time, so I gave it a shot.

Backend programming is in my opinion where the heart of a modern application lives. All the business logic is here, along with the data that makes each experience personal, and it orchestrates the events required for a good experience to feel like magic. The existing backend devs were sharp as tacks, so I soaked up all the game I could from them. We built a solid microservice architecture2 to power the site and mobile apps, with a series of message queues to handle background actions.

At one point we took an ambitious stab at building a social network-style interface for home buying, complete with a space for home buyers and agents to share listings for further discussion. We stored the data in MongoDB and used the MapReduce functionality to build complex but elegant declarative queries. Our application code used NodeJS and the Hapi server framework, and the entire thing was programmed in a functional style3.

A particularly passionate senior developer evangelized the juniors with his tightly held belief that OOP4 was the devil incarnate, complete with a crash course on partials, currying, closures, and the like. I am typically in the OOP camp nowadays, as it tends to be most places’ default pattern and I am not passionate enough to rock the boat, but doing functional programming was some of the most fun I’ve ever had writing code. A good abstraction is clean when everything fits, but building declarative pipelines of functions to perform a task feels like being a mad scientist building the ultimate Rube Goldberg machine. Once you built out your core functionality, it was startling to realize just how much logic could easily be reused to build out features quickly. The site we built with it is long gone, but I quietly remember it as something of which I was quite proud.

This was the job that sharpened my sword when it came to taking something from an idea to a complete program. At my internship I was exploring near exclusively, we never had any deadlines for launch dates and the tech was not driving revenue any time soon. This job was a different beast, as a small horde of people managed the requirements and timelines of the projects and there were yet more unseen folks who had a vested monetary interest that we build and deploy on schedule. This added layer of complexity manifested itself as tactical shortcuts that could be improved upon properly later, stripped features to focus on the core functionality, and a handful of late nights and weekends spent pushing code.

Soft skills could often be in short supply here. We certainly had a lot of fun and shipped technically competent features, but the culture could be somewhat aggressive. It was my first job, so I thought seeing code reviews regularly with 50, 60 comments, many of them about minutiae rather than guiding good architecture, was normal! I perpetuated the cycle myself when I marginally moved up the ranks and the older senior devs moved on. The jokes occasionally went a bit too far, and sometimes tempers flared as discussions devolved. I keep this in mind whenever I do code reviews or work through a technical problem with a colleague now, ensuring that there’s space for people to try and not need to have the right answer at their fingertips.

I made a ton of friends at this job. Our happy hours were the stuff of legend, and they definitely made all the crazy times worth it. Shoutout to all the other wonderful souls that made up this office.

This was also my first experience with remote work, as I split my time between Norfolk and Richmond near the end of my tenure. This was one of the main reasons I started looking for something local to Richmond, as I had yet to develop the time management skills needed to be productive remotely.

Big Business

I wanted to try something new after a few years into my first role, so I joined one of the local big corps that was positioning themselves as a tech-first organization. My team was a small squad nestled in the typical corporate structure of departments, verticals, orgs, and the like.

This job was pretty non-invasive to my life in a wonderful way. It was very 9-to-5 oriented, aside from the occasional late-night deployment. The work was low stress, and I went on a ton of walks during my lunches and read plenty of books as I enjoyed salad or pizza from the cafeteria.

My team at this job rocked, and we had a lot of fun together. Many of us played music, so a few nights saw us in a garage with a couple guitars and a drum kit. We went on a few trips together to visit different offices and always had a good time.

The tech role was similar fare to my previous. I made a lot of NodeJS services with Hapi, maintained a handful of legacy projects in tech stacks with which I had no experience, and made the occasional foray into our frontend Vue code. The platform was geared towards internal users, so the scale was considerably less than my previous role which was consumer-facing. In turn, we had no real need to setup anything particularly complex for the vast majority of our use cases and after a while I felt like I was growing stagnant with my skills.

During my time here, I volunteered with Microsoft’s TEALS program through CodeVA. I partnered with 2 other software developers and we taught a basic programming course to a high school in Virginia. We spent a semester going through the building blocks of programming: variables, boolean logic, conditionals, etc. with a visual language called SNAP. We taught our classes remotely, but a few times we made the drive out to the county to participate in the classroom. I tried my best to encourage those that were really interested to try their hand at programming, and framed things as best I could as to how it would relate to their interests. Near the end of our time together, we organized a field trip to our office and showed them what a day in the life of a dev looks like.

This experience translated nicely when the pandemic forced us all to go remote in 2020. There was an internal group that focused on outreach to local schools, so the TEALS volunteers paired up with them to build an HTML/CSS course aimed at middle schoolers for employees’ kids that were stuck at home. We taught the course a few times, using interactive web editors to build simple websites together. I enjoyed seeing the youth get excited over building pages for their favorite music or sports team with simple tools, the ones that would be recognizable to a generation of programmers who typed their first line of code into a Myspace profile.

I saw really great leadership here. Our team lead positioned each person on a path to grow their skills in a way that aligned with their goals and complemented their niche on the team. My biggest failure here was ultimately not being able to connect the work we were doing with the purpose of the business. One of the better pieces of feedback I got during my time here was that technical skills can only go so far. Understanding how software connects to the bottom line is where the real leverage on leading a group towards success lies. However, I wanted a job that was focused on building technology that was the star of a business, rather than powering things peripheral to their purpose. I moved to Philadelphia around this time, so I looked for tech companies in a new market.

Live

A few months into my life in Philly, I accepted an offer for a Senior Developer role at a local social media outfit. The main product was a suite of consumer-facing dating and social apps, along with a live-streaming video platform. I was placed on a scrum team focused on building features for the live video community. The technology stack was reasonable but had grown in complexity over time as new products launched and performance bottlenecks were patched. I relished being able to dive into the codebase so that I could learn about the savvy scaling solutions the teams had implemented, and how the design of such systems works in practical settings.

I spent a few years being a dev on this system and shipped quite a few features. The most interesting aspect of this time was hitting scaling bottlenecks and working through them. One of my first projects was to build out a microservice that would return documents to users with specific targeting based on their location, language, profile settings, etc. When it initially launched, the users’ requests were served in 100ms at best, a few seconds at worst, with ECS tasks in the double digits.5 This feature was used on our landing page, and degraded the load time of the entire site when it was performing poorly.

I used a few different caching strategies to remedy the response time, my favorite piece was a memory cache synchronized across all the tasks in the tier that refreshed itself whenever a write event occurred. This greatly reduced the time it took for a user’s search, and further memory caching for evaluations brought the average response time down to 10ms with 2 ECS tasks. Implementing this fine tuning to performance was incredibly satisfying, and I was glad that someone cared enough about our technical performance to give us the resources to fix it properly. My QA partner and I ran tests on the service for months as we diagnosed various problems and patched them. We walked away from the situation fulfilled, and better developers than when we started. This service has not spiked past 15ms in over 3 years.

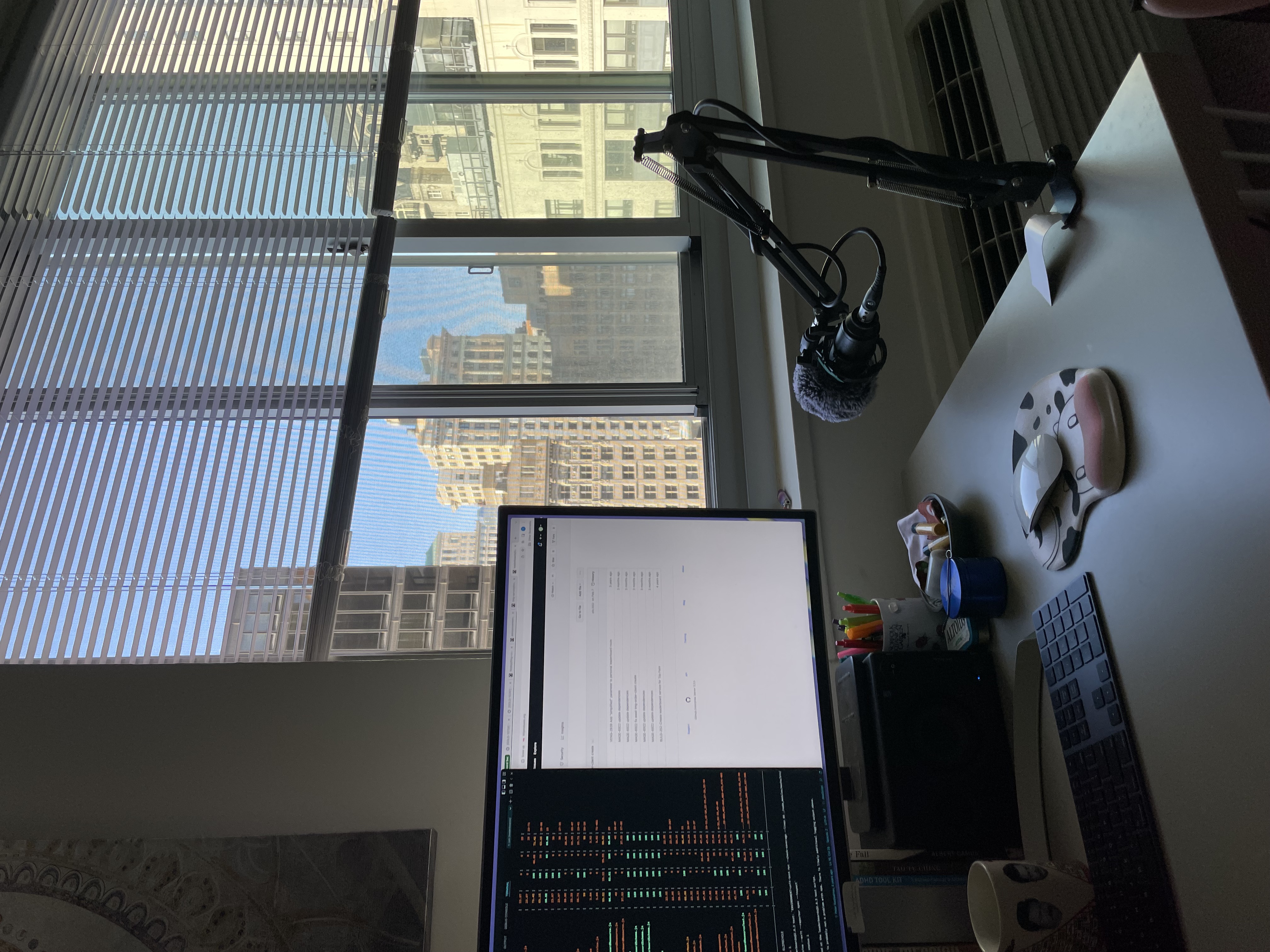

Time moved on. We shipped plenty of features together, patched bugs, and handled getting things stable when something blew up. It’s no secret that Tech has not had the best few years, and a lot of the faces have changed through new roles and layoffs alike. My team has two original members, myself included. I’ve been leading the team for a little over a year and a half and I enjoy it. I’ve had a lot of bosses and long-held opinions on things that worked and what didn’t work; this is my chance to take a shot at doing it right. I do my best to be honest and allow my team to do what they need to do without any micromanagement. There are areas I know I can improve in, and I’m excited to get better at it.

I focus less on developing features with my code nowadays and more on things that need to be done to steer our projects in the right direction. It’s an interesting mindset shift, and I find joy in being able to help my teammates directly with my efforts rather than working on code in isolation. My peers and I guide the architecture of the platform as new things are added, which presents challenges that require a good mental model and technical understanding to address. The things we have to figure out are genuinely fun to untangle.

I’ve worked remotely my entire time here, my longest-tenured job in the industry. I had to do some serious soul searching to be productive in a self-managed environment. The strategies I developed during this time are documented in my series The Path. It’s wonderful not having a commute, and I love the flexibility of being able to adjust my working hours as needed to accommodate things I need to do in my daily life. Our team is distributed all over the globe, allowing us to connect with people who have different cultures and viewpoints, reducing our blind spots when building apps for a global audience.

Future

I started this career by being curious and tinkering, without any foresight into where it may lead. I’m thankful that the craft is always evolving, and there’s consistently some new development to learn. As I write this, I have an AI agent open in my text editor, the latest gadget technologists are fiddling with. Those outside of the industry may not understand how quickly adopted and deeply ingrained AI tools have become in software development, but over the past two years we’ve gone from chatbots being a whimsical tool whose output needed heavy scrutiny to fully-fledged autonomous agents writing production-ready code with the correct guidance. For the most part the output of these tools has been good and steadily improving.

However we’re in a strange time, when every talking head in tech is either proclaiming that agents will completely replace the people in software development, or that AI is all hype, a waste of time and resources. After working with AI for some time, I am confident in saying that it’s a fallacy to believe that any agent on the market can replace a software developer without oversight. But I can easily see a world where we get more work done with less people, reducing the need for and raising the bar of what it means to be a junior dev. I worry for the large swaths of folks entering tech based on the 2010s promise of guaranteed employment and good salaries. I certainly wonder if I’d have been able to make the cut long enough to acquire the skills I did in my junior roles that’ve allowed me to be productive further down the road.

Companies are also laying people off in huge numbers, due to overhiring during the pandemic, fear in the global stock market, and tax changes to name a few reasons. The atmosphere around software development is starkly bleak compared to the preceding era of sunshine and rainbows, powered by low interest rates and VCs with seemingly endless cash. One has to have hope that the pendulum will swing back in the other direction at some point, but it’s hard to know if this is just another bubble pop that tech must ride out or if something more seismic is at play. With the industry-wide reduced headcount and the prevalence of AI eliminating junior roles, how can the next generation of programmers gain the real world experience needed to be able to guide agents properly for secure, scalable software platforms?

For me, the internet has been a great place for developing skills, making a living, and connecting with people. I’m grateful that I have been able to participate in building some of it. At its core, this is a place for people to be creative and share their perspectives. As the web is increasingly filled with walled gardens and corporate castles, I hope to be able to keep some part of it genuine.

Notes

-

Frontend vs Backend:

- Frontend is the code that runs on your device, displaying an app's data and allowing you to interact with it. These are websites, mobile apps, etc. Some frontend tech mentioned in this post: HTML, CSS, Angular, React, Vue.

- The backend is the code that runs on the server of an app's owner, and processes that data at the user's behest. Associated technologies in this post are NodeJS, PHP, and Hapi. Databases are also on the backend, of which SQL, DynamoDB, and MongoDB are examples.

- Microservice architecture is a style of designing backends where individual areas of responsibility (profile interactions, photo management, follower and following tracking, etc.) are grouped together and work in isolation, in contrast to a monolith which puts all the code for the entire application together. It's a powerful design that offers a lot of flexibility in regards to scaling, but it can often be too complex for most problems. The complexity gives it a bad rap.

- Functional programming - a mysterious programming style that computes data like an assembly line, each worker does their part and passes it along to the next until the job is done.

- Object Oriented Programming - a very popular programming style that organizes code into reusable "objects", akin to how real-world objects behave. In the words of Carl Sagan, "If you wish to make an apple pie from scratch you must first invent the universe."

- This is very slow and expensive